The Neuroscience of Op Art

Artists, like neuroscientists, are masters of visual systems. Through experimentation and observation, artists have developed innovative methods for fooling the eye, enabling flat canvases to appear three-dimensional, for instance. Neuroscience—and more recently the subfield of neuroaesthetics—can help to explain the biology behind these visual tricks, many of which were first discovered by artists. “I often go to art to figure out questions to ask about science,” says Margaret Livingstone, Takeda Professor of Neurobiology at Harvard Medical School. “Artists may not study the neuroscience per se, but they’re experimentalists.”

During the 1960s, Op Art—short for “Optical art”—combined the two disciplines by challenging the role of illusion in art. While earlier painters had created the illusion of depth where there was none, Op artists developed visual effects that called attention to the distortions at play. Abstract and geometric, their works relied upon the mechanics of the spectator’s eye to warp their compositions into shimmering and shifting displays of line and color. The Museum of Modern Art announced this international artistic trend in 1965 in a seminal exhibition titled “The Responsive Eye.” Since then, neuroscientists have continued to probe the mechanisms by which the human eye responds to these mind-bending works.

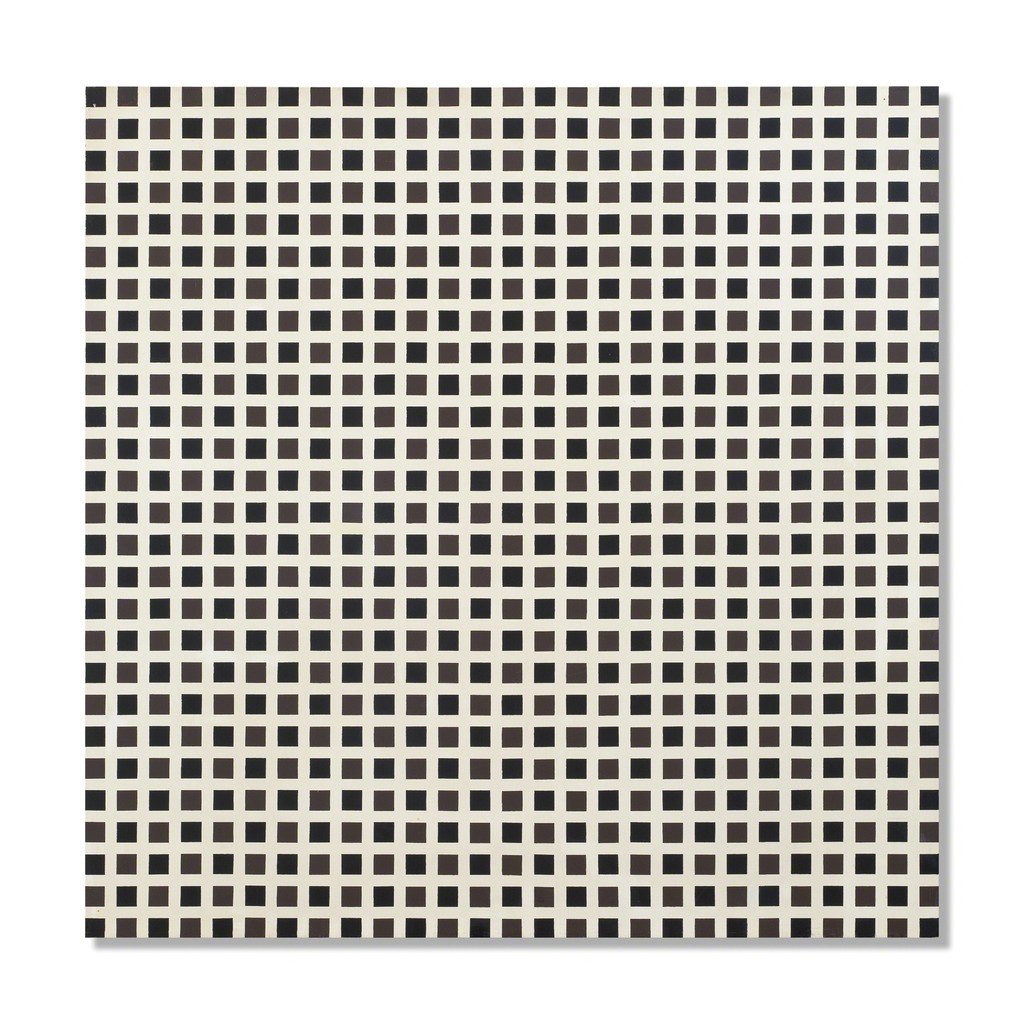

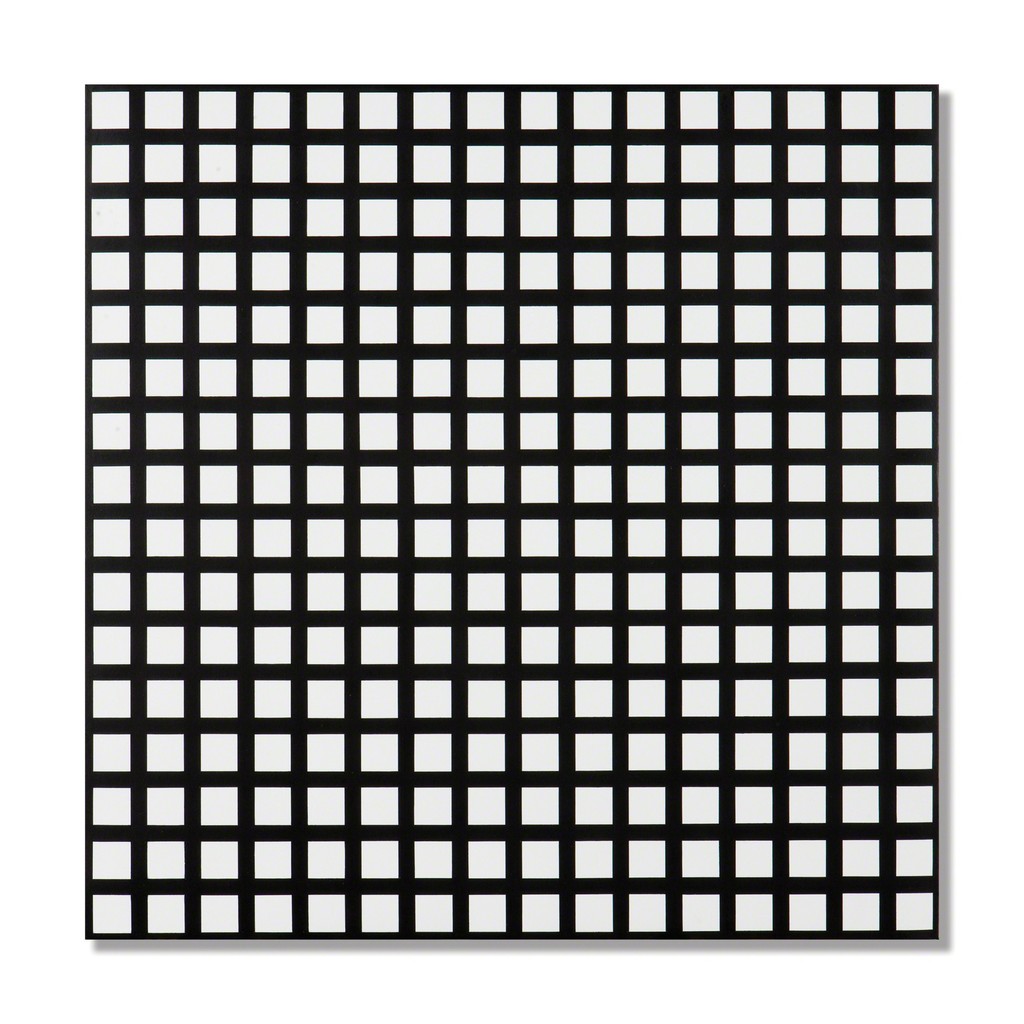

The notion that eyes are drawn to areas of contrast is foundational to visual neuroscience. Hard-edged boundaries between light and dark attract attention and become exaggerated through visual perception. A black circle on a white background, for example, will appear darker than the same black circle on a gray background—to scientists, this phenomenon is known as “center/surround antagonism.” A similar effect occurs in Hermann’s Grid, first discovered by the physiologist Ludimar Hermann in 1870, in which “ghostlike” gray squares flicker at the intersections of black-and-white matrices.

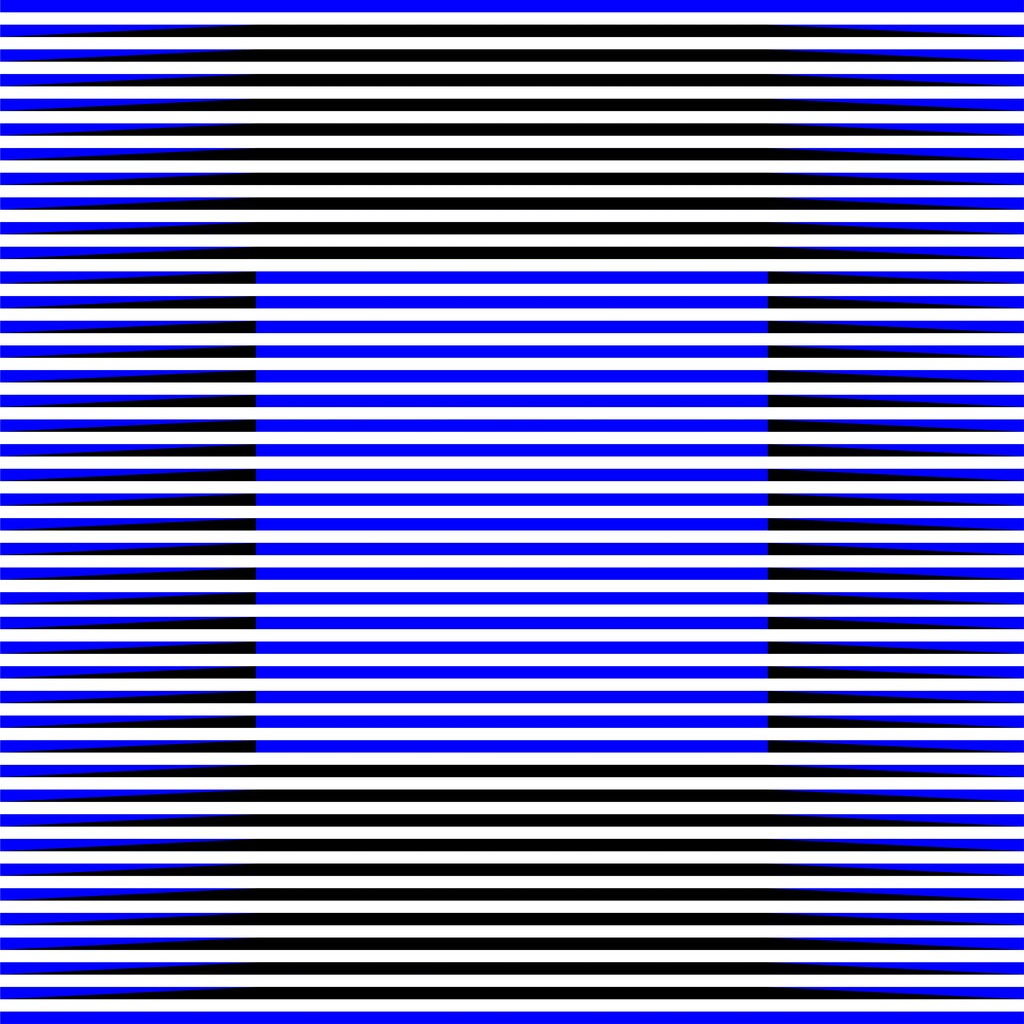

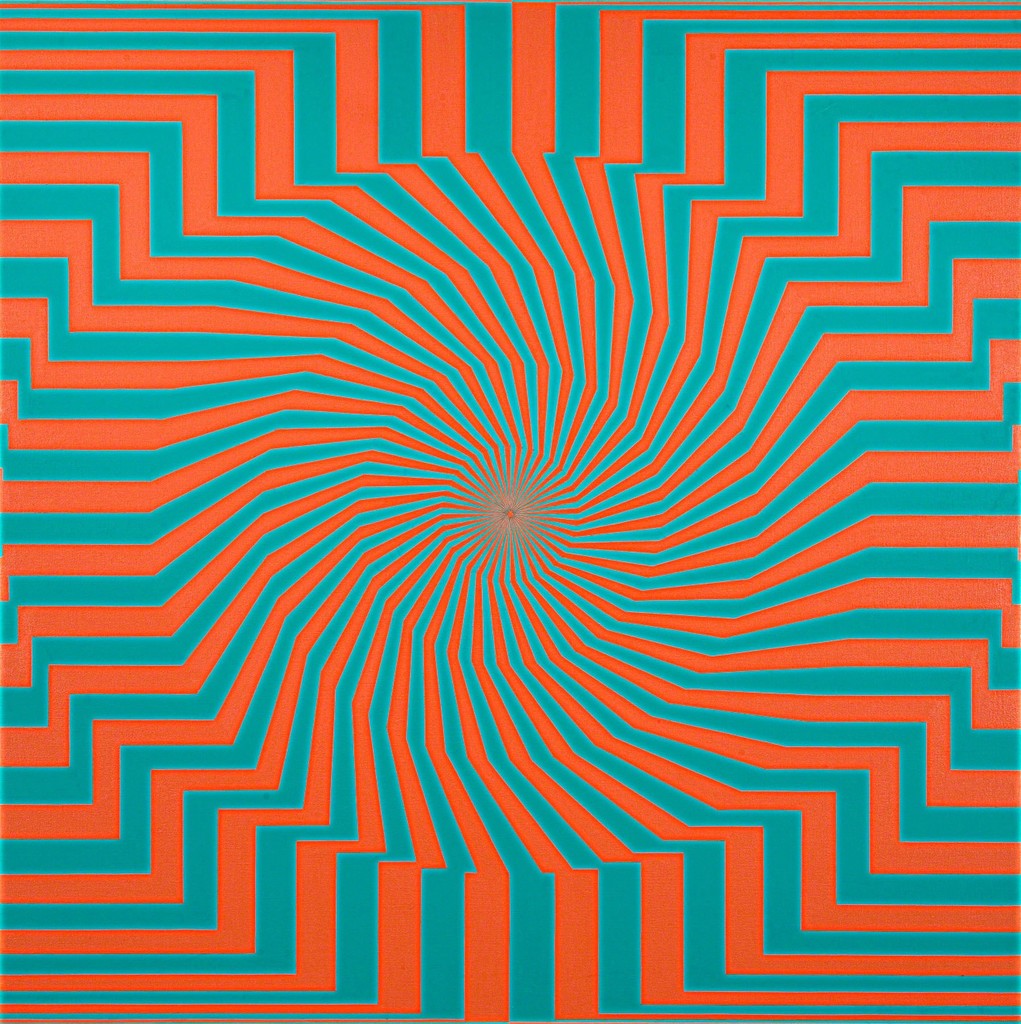

A comparative effect results from color contrasts. Stare at a blue-and-white-striped square for a few seconds, and chances are a yellow halo will appear in your visual field. “Yet there is no yellow in this work, none at all,” the Venezuelan Op artist Carlos Cruz-Diez once explained. “You see yellow because, when the blue hits the black, that is the effect on the retina. It’s an optical effect known as simultaneous contrast.”

Simultaneous contrast—the visual phenomenon behind the viral striped dress that appeared black and blue or white and gold depending on the viewer—is the principle that the perception of a color is dependent on what other colors surround it. Bright colors cast a shadow of their complementary (or opposite) color—blue contrasts yellow, red contrasts green—which is why the area surrounding the blue square takes on a golden hue.

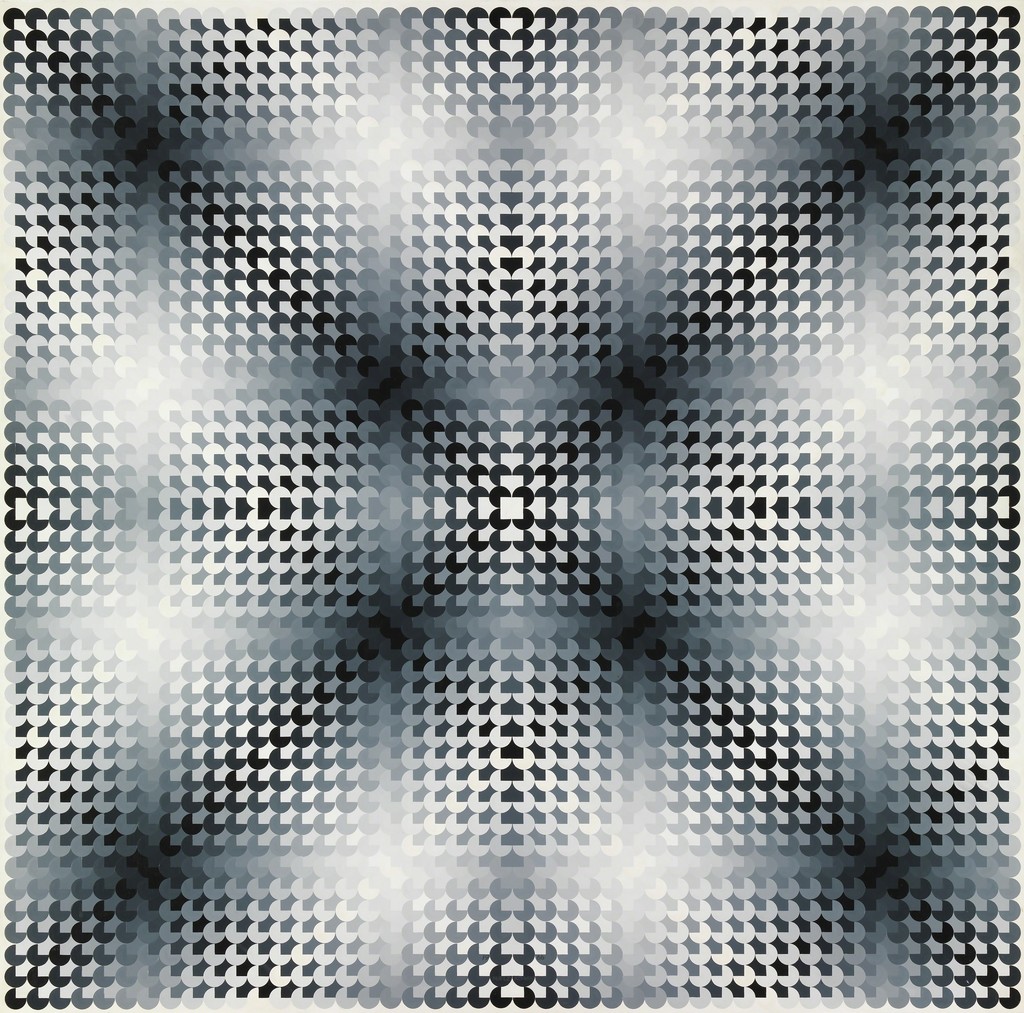

While illusions such as these are hard-wired in the human visual system, others emerge through lived experiences. By observing the natural world, the eye learns to interpret areas of low contrast (like clouds) as a transparent overlay atop areas of higher contrast (like the sky). American painter Edwin Mieczkowski takes advantage of this phenomenon, creating images that are simultaneously hard-edged and blurry. Mieczkowski’s Monobloc No. 1 (1966) tricks the eye into viewing areas of the painting that are low-contrast as misty layers in front of a uniform black-and-white background. The longer one looks at the painting, the more these areas seem to float towards the viewer and into the three-dimensional world.

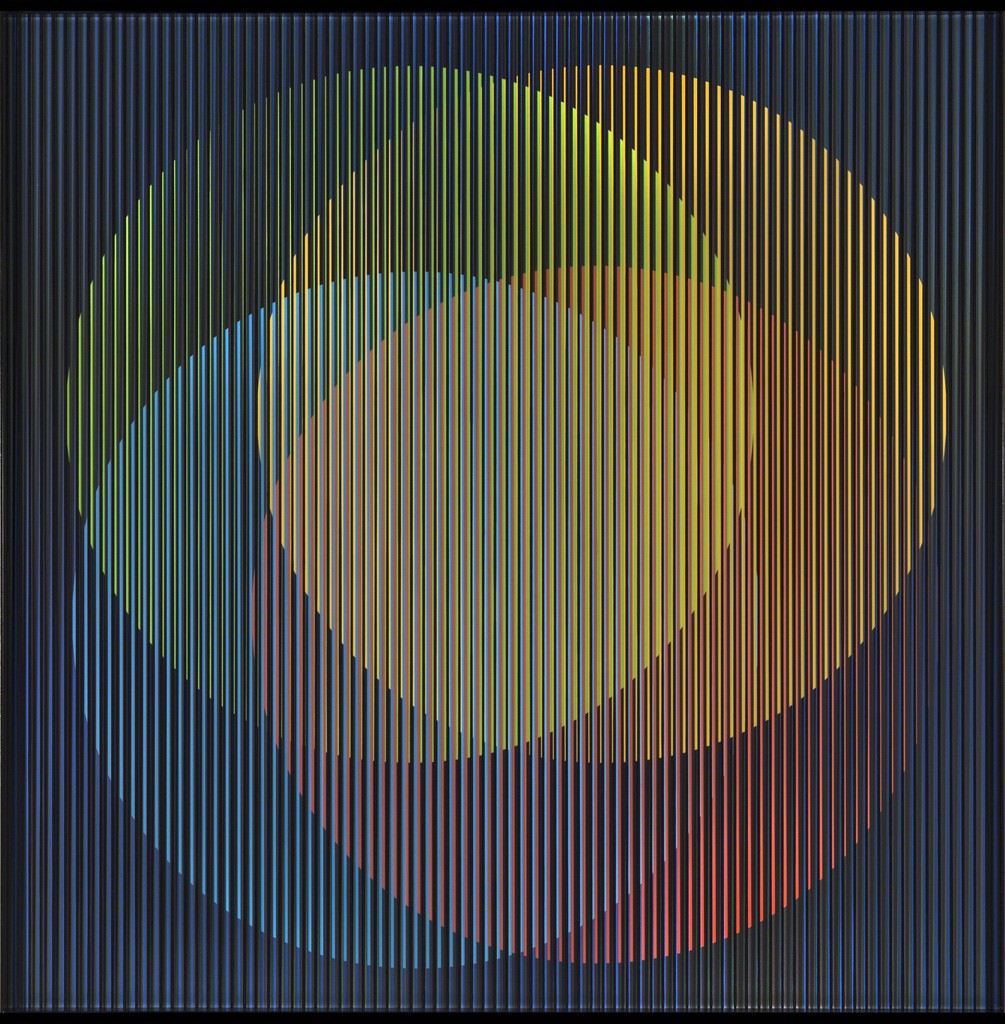

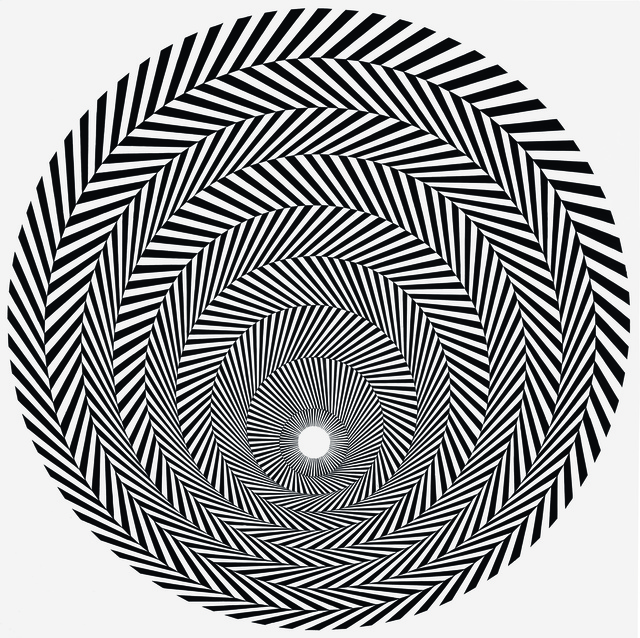

The appearance of motion in Op Art continues to drive research in neuroscience today. In 1957, Donald M. MacKay discovered that radiating lines (now called MacKay rays) create a glimmer of movement, though artists have used this mind-bending technique for centuries. One explanation for this effect lies in small, involuntary rapid-eye movements, called “microsaccades.” When presented with heavily patterned, high-contrast images, the eye (which is drawn to contrast) can’t focus its attention.

“My paintings are multifocal,” the British Op artist Bridget Riley once explained. “Not being fixed to a single focus is very much of our time.” Without a clear point to fix on, the eye involuntarily moves around an image, bringing elements of the picture in and out of focus.

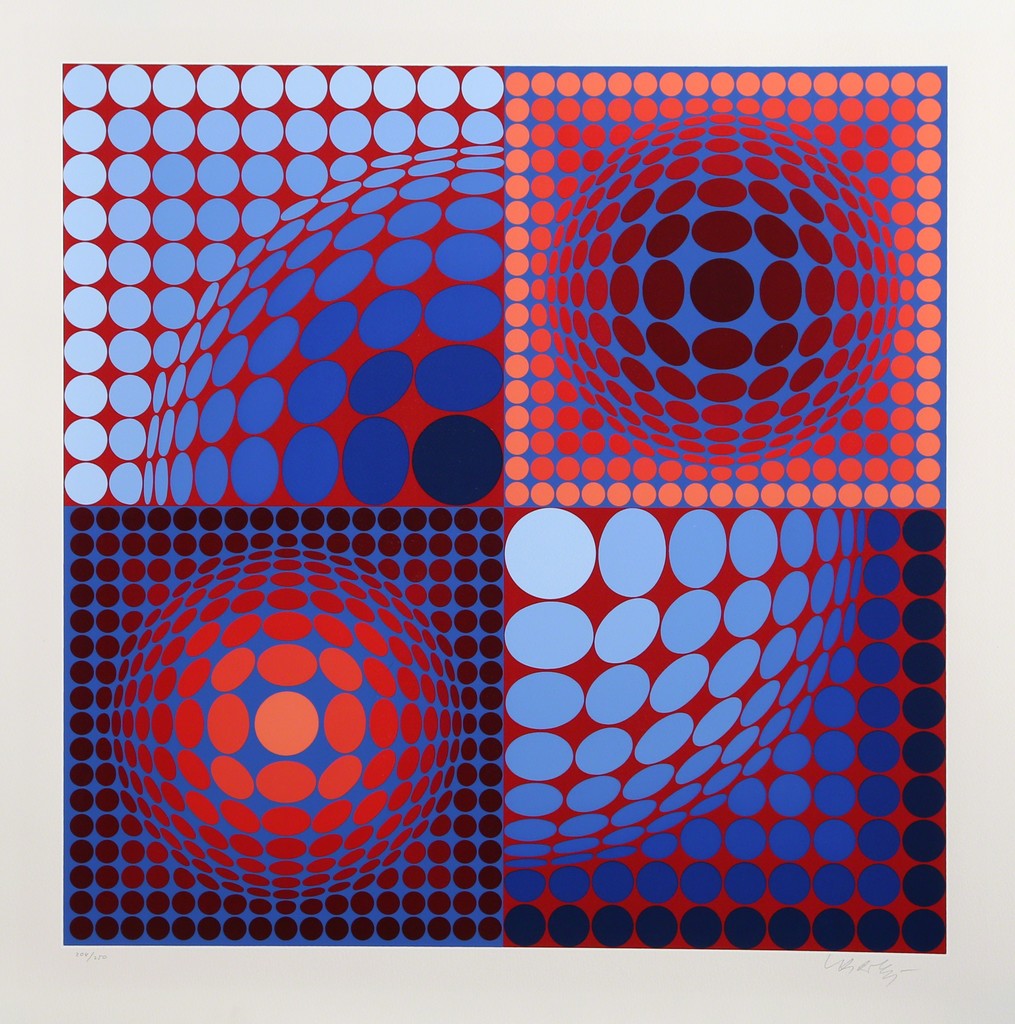

Op artists Marina Apollonio and Victor Vasarely applied centuries-old lessons of linear perspective to their abstract compositions in order to create illusory effects. Linear perspective is “a phenomenon of optics that light travels in a straight line,” says Livingstone, though she notes that artists discovered it before scientists were able to explain its effect. Around 1415, the Renaissance architect Filippo Brunelleschi is thought to have invented linear perspective, the first mathematical method for tricking the human eye. It involved arranging a composition around a vantage point that appeared to recede into the distance. The Op artists proved this method could be applied outside of representational painting. Vasarely used linear perspective to manipulate the colors and shapes of abstract forms, creating images that appear to balloon out into space.

While Op artists studied the science of perception, scientists have in turn looked to Op Art to ask questions about visual processes. Though their experimental techniques differ radically, their conclusions are often the same: The human visual system is not a mirror for the outside world. Rather, it is capable of seeing far beyond what is actually there.

—Sarah Gottesman